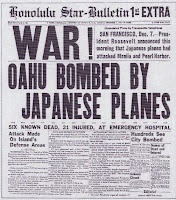

The horror of Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, a day President Franklin D. Roosevelt said would “live in infamy,” may have faded for many Americans, but not for the veterans who survived it.

“How can anyone forget Pearl Harbor? So many good American kids killed, wounded, maimed for life. We were unprepared. I hope Americans never forget,” said US Army Air Corps veteran Ed Cogan of Portland, who survived Pearl Harbor and later the Normandy Invasion, where he was nearly killed as a Glider Pilot.

Pearl Harbor was the worst attack on American soil before the jihadist terror attack of September 11, 2001. Some 2,403 American sailors, soldiers, marines, and civilians were killed. Another 1,178 were wounded. The Navy losses included eight battleships, three light cruisers, three destroyers, and four auxiliary craft. The Arizona, which still lies beneath the waters at Pearl Harbor, was struck by torpedoes and at least eight bombs, causing the death of all but 200 of the 1,400 crew members. Only a few American planes survived as the Japanese bombed and strafed inadequately protected airfields.

Ed Cogan was asleep in his bunk in the Army Air Corps barracks at Hickam Field on that peaceful Sunday morning when, about 7:55 a.m., the Japanese armada of 350 heavy bombers, dive bombers, and fighter planes attacked Pearl Harbor, their commander exulting “Tora!Tora!Tora!” on his radio to signal that the American forces had been taken by complete surprise.

“At first I didn’t know what was happening, then I realized – we’re under attack!” Cogan recalls. “I jumped up, pulled on my pants, and ran out of the barracks. I couldn’t believe it – the Japanese were bombing and strafing the airfield, the planes, the hangers, the barracks. We didn’t have any planes in the air and no effective anti-aircraft fire. We could see and hear the attacks on the ships in the harbor.

“At first I didn’t know what was happening, then I realized – we’re under attack!” Cogan recalls. “I jumped up, pulled on my pants, and ran out of the barracks. I couldn’t believe it – the Japanese were bombing and strafing the airfield, the planes, the hangers, the barracks. We didn’t have any planes in the air and no effective anti-aircraft fire. We could see and hear the attacks on the ships in the harbor.“We were running all over the place, trying to save the planes and not get killed. I was amazed at how low the Japanese were diving. They were so low and close, that a pilot made direct eye contact with me—and smiled. Laughing as he fired,” Cogan recalls.

“The initial attack broke off– but then there was a second wave. We had no defenses. We were shooting rifles and hand guns at dive bombers and fighters. We saved only 3,4 planes. We lost a lot of good men. We were unprepared. It was awful.”

Cogan, a native of Bath, Maine, the son of a cantor who served the small Jewish community there, had enlisted in the peacetime Army Air Corps in 1940 because he dreamed of flying. He considered himself lucky not to be hit in the attack. But in the Normandy Invasion almost three years later, as a Glider pilot, his luck would run out.

On June 24, 1944, D-Day+18, his first and last combat mission ended as so many glider landings ended—with a terrible, deadly crash, Glider pilots having one of the highest casualty rates in WWII.

Cogan suffered near fatal injuries, almost every major bone in his body broken. He awoke from a month-long coma in an English hospital, with no memory of anything after the crash itself. He was informed his co-pilot was killed.

He was transferred to an Army hospital in Massachusetts. While there, he saw a beautiful young woman named Annette working in the PX, and “it was love at first sight,” Cogan says. “Seven days later I proposed; she accepted; and we were married.”

He was transferred to an Army hospital in Massachusetts. While there, he saw a beautiful young woman named Annette working in the PX, and “it was love at first sight,” Cogan says. “Seven days later I proposed; she accepted; and we were married.”After two more years of treatment at various hospitals, Cogan was found totally disabled and medically discharged.

He and Annette moved to California, founded a successful book distribution business, and raised two daughters, before retiring and moving to Portland, OR, to be nearer to the family of one of their daughters.

As Pearl Harbor Day is again remembered, does Cogan, now 88, regret the military service which nearly killed him, disabled him, and left him with a lifetime of pain?

“Oh, no. Never. I consider myself extremely lucky,” says Cogan, a warm and friendly man with a very large smile.

“ First, I’m lucky to be alive. Second, I had the chance to defend my country with some really great guys. And,” he adds with a twinkling eye and broad smile while nodding toward Annette, his bride of some 65 years: “Just look at the great girl I got.”

[Rees Lloyd is a longtime civil rights attorney, and an activist in veterans affairs]

Tell ’em where you saw it. Http://www.victoriataft.com